Hurray for the Riff Raff

It had been a successful, if tumultuous, ride for Alynda Segarra, who’s been spreading a new kind of roots-conscious folk music across the country from her adopted hometown of New Orleans. But as far as the Bronx native had come with her band, Hurray for the Riff Raff, there was still a missing link to her story. “The more I toured, ending up in the middle of nowhere bars from Texas to Tennessee,” said Segarra, “I just started feeling more and more like, I don’t belong here, I gotta get back to my people, you know?”

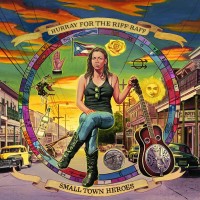

After many years in New Orleans, Segarra found herself getting antsy. Hurray for the Riff Raff had four albums under its belt, with the last one, Small Town Heroes, featuring “The Body Electric,” a song that NPR’s Ann Powers called “The Political Song of the Year” in 2014. Yet even though her musical career had begun by running away from home at 17, busking for survival and honing her craft through dreams of Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Memphis Minnie, and Woody Guthrie, Segarra realized she is a Puerto Rican kid from the Bronx with a different story to tell.

To find her way back home, Segarra became the willing vessel for a character she calls “The Navigator,” from which her new album takes its name. She describes The Navigator, a/k/a Navita Milagros Negrón, as “this girl who grows up in a city that’s like New York, who’s a street kid, like me when I was little, that has a special place in the history of her people.” Through The Navigator, the listener hears an ambitiously interwoven, cinematic story of a wandering soul that finally realized she needed to connect with and honor her ancestors.

Segarra quickly went to work with producer Paul Butler, whose work with British soul singer Michael Kiwanuka she deeply admired, to capture the cinematic, old but new quality she wanted. It also meant assembling a core group of percussionists like Kansas City-based Juan-Carlos Chaurand and Devendra Banhart’s drummer Gregory Rogove to play everything from Cuban to Puerto Rican to Brazilian backing beats. The result is an interconnected set of introspective songs, grounded in Segarra’s eclectic rustic root style, yet adorned by elements of son montuno, plena, and a kind of Mink De Ville retro-doowop rock.

Segarra drew early inspiration from cult favorite Rodriguez, a Mexican-American who translated working-class stories from Detroit into powerful rock ballads, and the Ghetto Brothers, an underground band from the 1970s South Bronx who stitched Puerto Rican nationalist messages into a rough-hewn fabric of Santana and Sly and the Family Stone Afro-Caribbean funk. She reached back to her cultural ancestors in the form of the radical political group the Young Lords and the salsa singer Héctor Lavoe. “I would just try to have the rhythm in my head and write the lyrics,” said Segarra. “Then I went back and added everything else, it was like poetry?”

Poetry permeates The Navigator, like when Segarra juxtaposes the feeling of growing up in a box in the sky on the 14th floor of an apartment building with the feeling her father had flying for what seemed like an eternity in a propeller plane from Puerto Rico to New York in the song “14th Floor.” Or when, in the elegiac piano-driven ballad “Pa’lante,” named after the Young Lords newspaper that showed the way forward, she inserts the sampled voice of legendary poet Pedro Pietri reading from his seminal opus “The Puerto Rican Obituary.” The Navigator is a restless observer, perched at the nexus of Allen Ginsberg’s East Village and the Nuyorican Poets Café, confessing the blues and dancing the punky salsa steps of a lonely girl, a hungry ghost.

Like a song-cycle from an imaginary Off-Broadway musical, The Navigator rises from the ashes of loneliness and striving, honky tonks and long walks by the river of urban dreams. From the wistful melancholy of “Life to Save,” to the stubborn resignation of “Nothing’s Gonna Change That Girl,” Segarra’s voice speaks with a husky weariness that coexists with a naïve curiosity. It’s the voice of a rebel who wanted everyone to think she was so tough, and nobody could take her down, but at the same time was yearning for love and magic, some kind of an awakening. Long-time Riff Raff fans should feel at home in The Navigator’s World. There’s always been a little bit of syncopated Caribbean strut to down home rock and roll, Appalachian rags share a similar root with Spanish troubadours and the blues is the same in any language. On The Navigator, Segarra’s voice has never been more soulful, whether she’s decrying urban gentrification on “Rican Beach” or mourning the lies people tell on “Halfway There.” Like the moment we’re living in, The Navigator is as much about the past as it is the future.

With its 12 tracks and its Travelers, Sages, and Sirens, the album comes straight at you from the intersection of apocalypse and hope. This album rides Patti Smith’s high horse while straddling Chrissie Hynde’s thin line between love and hate. Segarra may lament the Trumpsters who want to “build a wall and keep them out,” but she knows that, like the outcasts she embraces, “Any day now/I will come along.” There’ll be no more hiding at the dimly lit intersections of class, race, and sexual identity—now we will all come into the light.

“I feel like my generation, through groups like Black Lives Matter, is really focusing on that type of intersectionality—if one of us is not free, then none of us are free,” said Segarra. “The Navigator’s role is to tell the story, tell it to the people who don’t know their own story, so they can be free.”