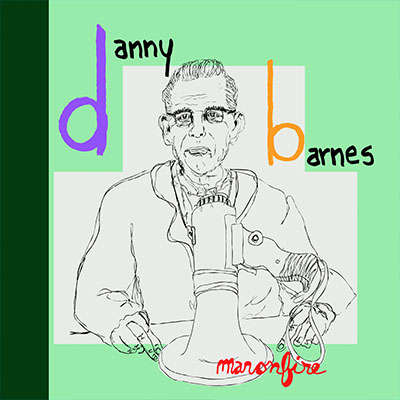

Danny Barnes’ “Man On Fire” is out now! Watch “Hey Man” Clip Starring Dave Matthews.

“A clever lyricist with a punk-rock past who understands the raw simplicity of a good country tune.” – Rolling Stone

“While many players use the banjo to show what they can do, Danny Barnes uses it to show who he is—something so rare that we have to look back decades for comparisons.” – Bluegrass Today

Banjo virtuoso Danny Barnes releases his new album Man On Fire today alongside a video for his single “Hey Man” that stars the record’s executive producer Dave Matthews. Directed by longtime Dave Matthews Band lighting designer and video director Fenton Williams, the video has Matthews playing the part of a lonesome vagabond searching for a place to lay his head.

In an interview with Billboard, Barnes says, “[Matthews] and I were thinking that we ought to do a video, and he’s such a good actor. Dave’s really great with facial expressions.” Of the video’s plot, he adds, “A lot of my poetry is about being stuck in that moment where you don’t really know what you’re gonna do. It deals a lot with someone trying to find dignity as a poor person.” Barnes encourages fans to visit and get involved with the charities Mary’s Place Seattle and the National Coalition for the Homeless.

Man On Fire features Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones on bass and mandolin, Bill Frisell on guitar, Matt Chamberlain on percussion, and Matthews himself on vocals and Wurlitzer. It is available for purchase HERE.

Originally from Texas, Barnes was a founding member of the influential roots-punk band the Bad Livers before relocating to the Pacific Northwest. He has been hailed as “smart, literate, innovative, and endlessly creative” (No Depression) and “A clever lyricist with a punk-rock past who understands the raw simplicity of a good country tune” (Rolling Stone). In 2015, Barnes was awarded the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass, hailed as “one of bluegrass music’s most distinctive and innovative performers.”

MORE ON MAN ON FIRE:

“Normally I work by myself,” says Danny Barnes. “I’ve learned to make records pretty quickly on my own over the years, but this time around I wanted to slow things down and open up the process to a circle of friends whose musical input I really value, to collaborate with a small handful of artists I consider to be true masters.”

Take a glance through the liner notes of Man On Fire, Barnes’ remarkable new album for ATO Records, and you’ll be sure to recognize quite a few of those masterful friends. There’s Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones, who contributed bass from London; jazz pioneer Bill Frisell, who laid down guitar in Brooklyn; session wizard Matt Chamberlain (Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie), who cut drums in LA; and executive producer Dave Matthews, who helped shepherd the whole collection from the very beginning. As star-studded as the album may be, it’s Barnes who shines brightest throughout, his virtuosic banjo and unassuming vocals front and center as he delivers poignant portraits of everyday folks struggling to get by in a world that’s been rigged against them. The songs here walk the line between past and present, fusing old-time tradition with modern experimentalism as they draw on a wide swath of American musical history, from Appalachian folk and Memphis rockabilly to Kentucky bluegrass and Bakersfield country. Ably guided by the subtle touch of producer Geoff Stanfield (Sun Kill Moon, Firehorse), the resulting collection manages at times to be both hilarious and heartbreaking, reaching out for hope wherever it appears but forging ahead with dignity and self-respect even when it’s nowhere to be found.

“To me, the fundamental question of life is, ‘How do you lay your burdens down?’” says Barnes. “There are so many powerful entities stacked against a person, especially a regular, unmoneyed person, but I think that just by realizing what’s happening to you, by recognizing the forces at play, you can start to regain some of your power.”

Growing up in rural Texas, Barnes learned firsthand what it took for working class men and women to survive. The son of an iron ore miner-turned-tractor salesman, he spent much of his childhood around farmers and tradesmen, which led to a natural affinity for the kind of earthy, organic music that reflected their stories. Already a prodigious banjo and guitar player by his teenage years, Barnes left home to study audio production at the University of Texas in the early ’80s, and it was there in Austin that he launched the Bad Livers, a groundbreaking trio with a wildly eclectic sound that mixed bluegrass, punk, jazz, and metal. Hailed by Rolling Stone for their “striking blend of virtuoso flash and poignant simplicity,” the group would release seven studio albums during their decade-long run, earning praise everywhere from The Washington Post to The Times of London and carving out a path for future string band genre-benders like The Avett Brothers and Old Crow Medicine Show along the way.

When the Bad Livers dissolved in 2000, Barnes embarked on a new chapter, touring and recording under his own name and collaborating with a wide range of prominent songwriters including Bela Fleck, Lyle Lovett, Robert Earl Keen, Dave Matthews Band, and members of the Butthole Surfers, Dead Kennedys and Ministry among others. As a solo artist, he released more than a dozen critically acclaimed record, took home the prestigious Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo, and helped redefine the instrument’s possibilities with an innovative approach he dubbed “folktronics.”

“I liked to imagine this guy in a rural area who discovered all of this electronic machinery from the ’50s and ’60s just laying around in his yard,” explains Barnes, who now calls Washington State home. “I wanted to make songs that sounded like some hillbilly got a hold of a bunch of oscillators and stuff and incorporated it all into a hoedown. That weird conflict of old and new has always been a part of my music.”

Indeed, Man On Fire is no exception. Barnes’ characters on the album are timeless figures grappling with the essential questions of their humanity. They could live in any era, and though their portrayals are richly detailed and grounded in modern reality, the reckonings they face and revelations they come to are universal in nature.

“I’m an unusual guy in that I don’t like to write about myself much,” Barnes explains. “A lot of my ideas come from reading the Bible and observing the world around me. On some level, we’re all just trying find beauty and happiness and fulfillment within a system that doesn’t necessarily have our best interests at heart, and I think the role of music and art and poetry is to provide catharsis in the face of all that.”

In the case of Man On Fire, that catharsis begins with funky album opener “Awful Strange,” which finds its narrator coming to terms with the reality that his life and his labor are cogs in someone else’s wheel. It’d be easy to give up in the face of such a realization, but in Barnes’ telling, that knowledge comes with possibility, and the song, like much of the album, manages to find a glimmer of promise in otherwise desperate straits. The hypnotic “Coal Mine,” for instance, hints at vintage Alan Lomax field recordings in its Sisyphean portrait of keeping your head up even when escape seems impossible, while the modal “Zandapp,” which features Matthews singing the verses, finds a ray of light against the darkness in a little Austrian motorcycle, and the infectious “It’s Over” tumbles out of the speakers in a melodic cascade as its narrator keeps the faith that he’ll make it through the storm he finds himself in.

“Country, bluegrass, rock and roll, it was all designed to provide real service to humanity, to be a balm against the cruel reality of this physical plane,” says Barnes. “It was a doorway to a vast cosmos that could give you strength and lift you up. My mother grew up on a sharecropping farm in central Texas, and they’d pull the car up to the house at night and run the radio off the battery just so they could listen to the Grand Ole Opry. People forget how much this music used to mean because nowadays it feels more like advertising or lifestyle branding, but I’m trying to capture that relevance, that spiritual connection, that essence of where it came from.”

While Barnes touches on the political with the album, it’s never about left vs. right, but rather have vs. have-not. The timely “Enemy Factory” finds history repeating itself as the ruling class tells the rest of us who to hate, while the lilting “Mule” imagines life on the farm from a working animal’s perspective, and the wistful “Hey Man” relays the tale of a drifter just searching for a warm place to sleep. It’s perhaps the heartbreaking “The Less That I Know,” though, that most embodies the album’s central conflict: do we bear witness to the pain and suffering of this world, or do we shield ourselves by looking away when it all becomes too much to endure?

With Man On Fire, Barnes insists that we not only bear witness, but that we also step outside of ourselves, that we treat our brothers and sisters with the empathy and grace they deserve. In that regard, it makes perfect sense that he would open up the album’s creation to a circle of trusted friends and collaborators who could bring their own perspectives and histories to the music. These are troubling times, no doubt, but Danny Barnes wants you to know we’re all in it together.