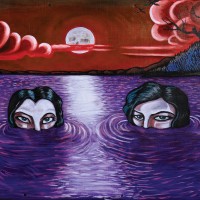

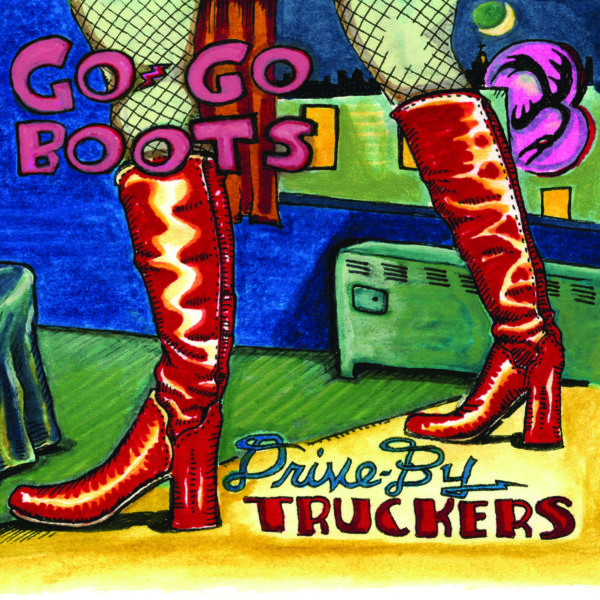

Go-Go Boots

Drive-By Truckers

Far more than on any of the Drive-By Truckers’ previous albums, Go-Go Boots rises like smoke from the old Muscle Shoals country-and-soul sound. Having recorded with Bettye LaVette and Booker T. Jones, and having spent a lifetime listening to classic soul albums by Bobby Womack, Tony Joe White, and especially Eddie Hinton, it was inevitable that the Truckers eventually produce this album.

We knew they were pin-your-ears-back rock and roll. But here in Go-Go Boots, the Truckers are country, and here, too, the Truckers are soul and rhythm and blues. It looks funny, on paper – the words country/soul mashed up like that – but maybe in the end it comes down to this one shared ethos: the harder life gets, the more clamantly it calls for art, for music, for beauty – for the slow celebration of loss or pain that is mournfully, beautifully defiant.

It seems a paradox that while the Drive-By Truckers’ sound is so unique; it is still part of a greater and larger family. Some of the other greats – particularly in the South – were spawned from their culture, while others came from the deeper rootstock of the southern landscape itself. Of course in the long run the landscape has a significant say in what kind of culture develops; it’s all tangled together, all connected, and everything shares bits and strands of those fragments, again like a pastiche of random and beautiful genomes. Each of the three vocalists – Cooley, Patterson, Shonna – is distinct; each aches in its own way with sometimes gravelly and other times smooth sweet wistful broken-glass hurt and yearning and reluctant. Patterson’s songs, of course are almost always willing, in the great Southern tradition, to take on the Man – or anyone else – as are Cooley’s, when the cause is big and just.

Their sound – so distinctly theirs – comes nonetheless from history and the past. It’s all a big tangled beautiful mess, and it all comes out of Muscle Shoals, where, as Patterson’s father, legendary bassist David Hood, astutely notes, the South once did something right with respect to race relations, once-upon-a-time, and when it most mattered.

In their documentary, The Secret to a Happy Ending, Patterson speaks of the South’s “duality thing.” Visually, the documentary shows a symbolism of this duality nicely: the fecund green clamor of summer (play it loud), insects shrilling high in the canopy as if giving voice to a fever in the land that may or may not be a madness; and in winter, the bare raw limbs, the signature of a thing – things – going away. Similarly, the Truckers, while walking on the dark side of the street in their songs, seem, despite it all, unable to avoid stumbling into cathedrals and columns of light, as in Mercy Buckets.

A little about Go-Go Boots: it doesn’t make a lot of sense for me to wax long about what you’re going to hear. The incantatory, almost child-like refrain of clamant happiness, “I do believe/I do believe,” with its big-band rock-chord super-anthem kicking in, then – a song about family, and the memory of being loved – a rock song about one’s grandmother! – sets the tone for all that is to follow, fireplace poker bludgeoning be damned.

You hear the bona fide country in Cooley’s Cartoon Gold, complete with rambling banjo run, and the undefinable ache and wonder at life, in the vocals – and you hear the I’ve-been-done-wrong-by-life-bit-am-still-here, still-hurting, hurting-so-good slowing- down soul sound.

So many of the songs on this album will end up being favorites, and anyway, it’s not fair to say one song’s better than any other – but damn, the first Eddie Hinton song on this album – Everybody Needs Love – is awfully fine. The Truckers hardly ever cover anyone else’s songs, but here they’ve chosen two by their late friend, Hinton. This is a big deal and when you hear the two songs you’ll understand what a good idea it is. You’ll also see how directly their country-soul sound resonates with his.

What is country-soul? The glib description, “You can’t pin it down but you know it when you hear it,” isn’t very satisfying. It’s not enough to say it’s funky, or has “that slow steady soul beat, that drive.” It’s not enough, technically, to say it places John Neff’s pedal steel with Jay Gonzalez’ B-3 and piano, or, on other songs, his Wurlitzer – but that’s true enough, too. Maybe the best way to understand what country-soul is is to listen to Everybody Needs Love again. It’s got a great vocal reach – a beautiful, no-holds-barred straining greatness – mixed with the Memphis backside style of drumming-compliments of Brad Morgan – that Al Jackson made famous on Wilson Pickett’s Midnight Hour. Here, it’s perfectly in sync with the story, and the mood, the message. It’s got the great back-up chorus coming in, the piano and Hammond B-3 assuming greater authority, the farther into the song you go. We could be talking about genetic strands being inlaid, so deeply and intensely does this sound take over a listener. After only a couple of playings, it seems like the song inhabits you, has always been in you. This is what constitutes a classic.

The DBTs are getting to that age where, battered and scarred, they have deeper wonder for the fact that they’ve survived. They’re not any wiser – they were born wise, have always been wise, possessing the instincts (a gift of their landscape) that Flannery O’ Connor (who almost surely would have been a DBT fan) called “wise blood.” But with their old wisdom, they have the compassion of the survivors, now.

Sweet, you say? How can a song about a preacher bludgeoning his wife with a fireplace poker be sweet? Well, they are still the DBTs, after all. Maybe that one’s not the sweetest of the bunch. But even it has something intangible in the sound-something less dark, less desperate: something that is somehow fuller.

There’s something else in these songs – happiness. Not joy, but the rare, more sustainable and enduring thing, a happiness earned by exploring the darkness, and surviving.

Something undefinable has changed within the Truckers. They’re still rocking on, but a few more strands of lightness of being, and happiness, have infiltrated their being. They’re happier. Do not hold this against them, nor worry that it will corrupt their blues and rock, their snarl and anguish. Instead, the happiness will continue to whet these things – the things for which their old fans love them. Theirs is an earned happiness, and therefore does not temper or weaken their sound. Indeed, this new light forges the sound – the rock. You can hear it in every chord. It’s their finest yet.